|

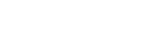

Why did you choose to specialize in otolaryngology among the various medical fields?Both my great-grandfather and grandfather graduated from Severance Medical School, so I have always felt a profound connection to Severance. Perhaps influenced by this legacy, I harbored a vague dream from a young age of becoming a doctor or medical professor. During my medical school years, otolaryngology stood out as the most exciting specialty during clinical rotations.Otolaryngology offers an incredibly diverse spectrum, treating patients across all age groups, from infants to the elderly, and encompassing both internal medicine and surgery. The field addresses everything from common colds to complex head and neck cancer surgeries and even emergency procedures for airway obstructions. Cochlear implants, for example, enable the restoration of lost body functions like hearing, while allergy treatments reflect its internal medicine aspects. The field’s breadth and impact were simply too fascinating to resist.What are vestibular schwannoma and external auditory canal cancer?Both conditions are rare diseases that affect the ear. Tumors and cancers can indeed develop in the ear, including in the external auditory canal, which refers to the ear canal. Each year, fewer than 1,000 people nationwide are diagnosed with these conditions, resulting in a shortage of specialists equipped to treat them.In 2014, a senior professor at Severance Hospital who specialized in ear tumors and cancers passed away unexpectedly. Although I had already developed a deep interest in the field, I found myself abruptly inheriting his responsibilities without the benefit of a proper handover. This sudden shift led to significant challenges and numerous trials and errors as I navigated the complexities of the specialty.

Due to the rarity of these diseases, it must have been challenging to master the surgical techniques, right?Cancers of the stomach, liver, and lungs provide relatively more opportunities for learning, as these conditions are more common and widely studied. In contrast, there are very few specialists focused on vestibular schwannoma or external auditory canal cancer. After my mentor passed away unexpectedly, I devoted myself to intensive training in the anatomy lab to refine the necessary surgical techniques.At the time, many of my mentor’s patients, who were already scheduled for surgery, faced wait times exceeding a year. While about half sought treatment at other hospitals or abroad, the remaining patients had no choice but to wait for me to perform their surgeries. To prepare, I repeatedly watched and analyzed my mentor’s surgical videos, practiced extensively in the anatomy lab, and rehearsed countless imagined surgeries in my mind before finally operating.After nearly two years of this rigorous preparation, I gained confidence in my surgical abilities. This intense period of training not only enhanced my skills but also paved the way for me to become the Director of the Surgical Anatomy Education Center.Is external auditory canal cancer more dangerous than other types of cancer?Cancer can develop in any tissue of the body. When it occurs in the skin of the ear canal, it is classified as external auditory canal cancer. This cancer is particularly dangerous not because of its biological nature but due to its anatomical location.The ear canal is positioned near several critical structures: the brain lies just above it, while the carotid artery and jugular vein pass directly below. A thin bone, barely one millimeter thick, separates the brain and carotid artery from the ear canal. In front of the canal are the salivary glands and the facial nerve. While this thin bone provides some temporary protection, once the cancer breaches it, the disease can quickly spread to these vital structures.This proximity to critical anatomical landmarks makes external auditory canal cancer comparable to a high-risk geopolitical situation. In South Korea, fewer than 100 cases are reported annually, and I personally perform surgery on approximately 30 of these patients each year.

Vestibular schwannoma is another rare disease that is not widely known. Can you explain it?Vestibular schwannoma is a tumor that develops on the auditory nerve, located deeper inside the ear beyond the ear canal. Similar to external auditory canal cancer, it poses significant risks due to its location.The auditory nerve directly connects to the brain, and as the tumor grows, it can extend into the brain, causing pressure and neurological dysfunction. While external auditory canal cancer in its late stages can be life-threatening, vestibular schwannoma may impair bodily functions by damaging the brain. Both conditions are severe and potentially life-threatening.Who is more likely to develop vestibular schwannoma and external auditory canal cancer?Unlike colorectal cancer, which is influenced by diet, or lung cancer, which is linked to lifestyle choices, these conditions are not strongly linked to diet, lifestyle, stress, or overwork. Instead, genetic factors play a predominant role. Mutations or issues with specific genes often underlie their development, making prevention through lifestyle changes challenging. A family history of these diseases significantly increases the risk.Vestibular schwannoma can occur even in children, highlighting its genetic basis. The incidence rate is approximately 1 in 100,000 for vestibular schwannoma and 1 in 1,000,000 for external auditory canal cancer, indicating their rarity.

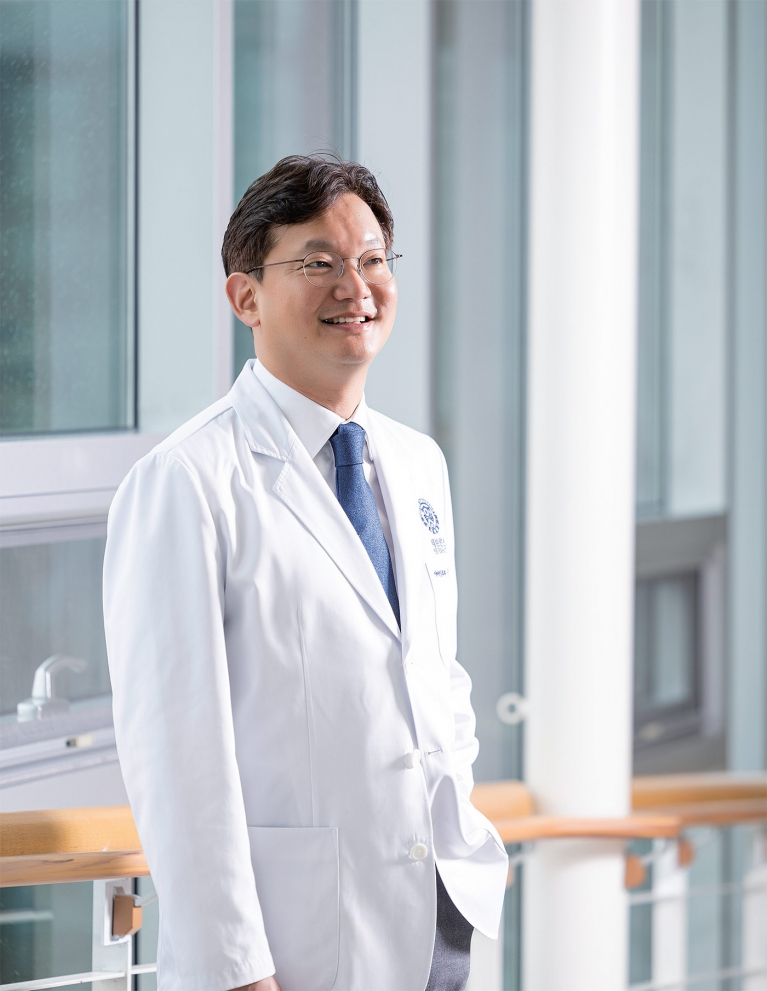

Is the surgery more difficult compared to other procedures?Yes, these surgeries are extremely challenging. First, removing the cancer without damaging surrounding critical structures, such as the brain, carotid artery, salivary glands, or facial nerves, is technically difficult. In advanced cases where the cancer has spread, surrounding structures may also need to be excised, significantly increasing surgical risks.Second, the surgeries carry a high risk of mortality in advanced stages, and even when successful, the likelihood of complications or disability remains high. Recurrence is common, particularly in later stages.The goal is to remove as much cancer as possible while preserving function, requiring precise surgical judgment. For external auditory canal cancer, the ear canal often needs to be removed, resulting in hearing loss. In some cases, the auricle (outer ear) must also be excised, leading to noticeable cosmetic deformities. Despite thorough preoperative explanations, the emotional impact and sense of loss for patients can be profound.In 2022, you developed an endoscopic technique for resecting external auditory canal cancer. How was it resected previously?In the past, surgery for external auditory canal cancer, even at stage 1, required removing the entire ear canal, inevitably leading to hearing loss. Questioning whether it was appropriate to rely on outdated techniques, I developed an endoscopic approach in 2022 to address this issue.The endoscope is equipped with specialized tools, including an irrigation device, suction-dissector, and shielded drill, allowing precise excision of only the affected area. Traditional methods removed large areas surrounding the cancer due to the limitations of older endoscopic and microscopic technologies. However, with the advent of 4K-resolution endoscopes, surgeons can now clearly visualize the site and narrow their focus.This breakthrough has enabled the preservation of unaffected structures, reducing the extent of hearing loss and improving cosmetic outcomes. Surgical techniques must evolve alongside technological advancements, and this innovation represents a significant step forward in the treatment of external auditory canal cancer.

|

The field seems even more conservative than expected. How did you overcome this?Over the past 15 years, the use of endoscopes in ear surgeries has grown exponentially worldwide. About a decade ago, a small group of surgeons, including myself and colleagues from the United States, Italy, and Australia, began applying endoscopy to vestibular schwannoma surgeries, some of the most complex procedures in our field.We formed a global network for endoscopic ear surgery, engaging in intense debates with established authorities and proving the efficacy of our techniques through surgical outcomes. After enduring criticism for a decade, we succeeded in shifting the paradigm.Today, the previous generation of experts is no longer invited to deliver keynote speeches at international conferences. Those roles are now occupied by myself and other members of our group. This shift mirrors the transition from surgeries performed solely by hand to robot-assisted procedures, which also faced initial resistance before gaining acceptance.It seems that bold shifts in thinking have ultimately benefited both doctors and patients.Absolutely. An important example is the simultaneous removal of vestibular schwannomas and cochlear implantation. Traditionally, these procedures were performed separately. Tumor removal poses a high risk of nerve damage, and combining it with cochlear implantation was once considered taboo.Additionally, cochlear implants historically interfered with MRI scans due to the magnet, complicating the detection of tumor recurrence. For decades, patients who underwent tumor removal often had to forgo essential MRI diagnostics. However, since the 2010s, technological advancements have allowed MRI compatibility with cochlear implants. Despite this, outdated beliefs persisted, and the idea of combining the two procedures remained controversial.By focusing on preserving the nerve and leveraging advancements in endoscopic technology, I challenged this long-held taboo. This bold shift in perspective has made simultaneous tumor removal and cochlear implantation a reality, ultimately improving outcomes and reducing the burden on patients.

Taking on such challenges seems risky. What drives you to pursue them?Pioneering surgeries and first-time successes are a double-edged sword. When a new procedure succeeds and is adopted by others, you’re seen as a trailblazer. However, if the outcomes are poor and the method isn’t widely embraced, you risk being labeled reckless—a butcher rather than a pioneer.Before attempting any new procedure, I conduct hundreds of surgeries using established methods to thoroughly understand their limitations. When I identify areas for improvement, I engage in extensive discussions and deliberations with colleagues. Only after building consensus and gaining confidence do I move forward, producing supporting papers and ethical documentation. This rigorous process involves numerous presentations, validations, and publications.Even being the first to succeed doesn’t guarantee immediate recognition from the academic community. Consistent evidence and collaboration with like-minded peers are critical. For instance, while I was the second surgeon globally to perform endoscopic vestibular schwannoma surgery 8 years ago, there are now about 40 related publications supporting the technique.I was the first in the world to perform simultaneous vestibular schwannoma removal and cochlear implantation. Following my success, three colleagues from the United States, Italy, and Australia adopted the procedure. Their participation validated the technique and accelerated its acceptance.You also serve as the Director of Surgical Anatomy Education Center at Severance Hospital. What does this role entail?Cadavers for anatomical practice are always in short supply compared to demand. At Severance, the hospital’s Christian founding background has resulted in a relatively higher number of donations compared to other institutions. These donations support not only medical student education, but also mock surgeries for clinical departments.There is a common misconception that cadaver use is limited to anatomy classes for medical students. In reality, cadavers are essential for training residents and refining the skills of surgeons. For example, neurosurgery residents cannot become proficient by merely observing senior surgeons. They must perform numerous mock surgeries to gain hands-on experience and develop the skills necessary to operate independently.Simply increasing the number of medical graduates does not equate to producing competent physicians. At Severance, cadavers are utilized efficiently, not just for student dissections, but also for anatomy training and mock surgeries across all clinical departments. My role as Director involves overseeing and managing this process to ensure that every donated cadaver is used to its fullest potential for both education and surgical training.

What is the government’s stance on the use of cadavers during recent conflicts in the medical community?A senior official from the Ministry of Health and Welfare recently claimed, “There are approximately 1,200 donated cadavers in Korea, but only 800 are actually used, leaving 400 unused.” This statement demonstrates a lack of understanding of the actual situation.The figure of 800 only accounts for medical student dissections. However, cadaver-based training occurs at multiple levels: students, residents, and even instructors require access to cadavers to hone their skills. To cultivate outstanding specialists, training must be repeated at every stage, from medical school to residency and even as assistant professors.Becoming a fully competent surgeon doesn’t happen overnight. A surgeon only reaches full proficiency after years of dedicated practice, typically at the level of associate professor. The government’s narrow view of cadaver utilization overlooks the critical role it plays in the ongoing development of skilled medical professionals.Isn’t it possible for the public sector to redistribute cadavers to areas where supply is lacking?This suggestion overlooks the unique and deeply personal nature of cadaver donation. Unlike organ donation, cadavers are donated to specific schools or hospitals designated by the donor. For instance, an emeritus professor from our institution might choose to donate their body to Severance Hospital. These arrangements strictly respect the donor’s wishes.Is the government proposing to redistribute cadavers by separating the head from the limbs? Such an approach is not only impractical but also fraught with significant ethical concerns.The idea of importing cadavers raises even more complex ethical dilemmas. While companies specializing in cadaver supply exist in countries, such as the United States and China, importing cadavers into Korea is strictly prohibited under current laws, primarily due to quarantine regulations. Even if the law were amended and stringent quarantine measures enforced, the complete prevention of new virus introductions would be impossible.Additionally, concerns about the ethical practices of cadaver suppliers persist. In the United States and China, there are unconfirmed but recurring allegations that these companies may exploit vagrants and homeless individuals. Is it justifiable to risk complicity in such unjust practices for the sake of advancing medical research?No matter how sophisticated our equipment and technology become, the foundation of medicine lies in a thorough understanding of human anatomy—a foundation that begins with dissection practice. As the director of a surgical anatomy education center, I find the tendency to undervalue the importance and significance of cadaver use both troubling and deeply regrettable.

As an ENT specialist, are you planning any further innovations?Beyond advancing patient outcomes through minimally invasive procedures, I am actively engaged in several experimental projects. One of the most promising areas is the development of diagnostic markers. Prostate cancer can now be detected using specific blood markers, eliminating the need for frequent and burdensome CT or MRI scans. I aim to develop similar diagnostic markers for conditions such as external auditory canal cancer and acoustic neuroma.Moreover, since surgery or radiation therapy alone is not always sufficient for a complete cure, I am also working on alternative treatment methods. The ultimate goal is to create a comprehensive solution that encompasses the entire spectrum of care, from accurate diagnosis to effective treatment.